Horst Cabal has risen from the dead. Again. Horst, the most affable vampire one is ever likely to meet, is resurrected by an occult conspiracy that wants him as a general in a monstrous army. Their plan: to create a country of horrors, a supernatural homeland. As Horst sees the lengths to which they are prepared to go and the evil they cultivate, he realizes that he cannot fight them alone. What he really needs on his side is a sarcastic, amoral, heavily armed necromancer.

As luck would have it, this exactly describes his brother.

Join the brothers Cabal as they fearlessly lie quietly in bed, fight dreadful monsters from beyond reality, make soup, feel slightly sorry for zombies, banter lightly with secret societies that wish to destroy them, and—in passing—set out to save the world.

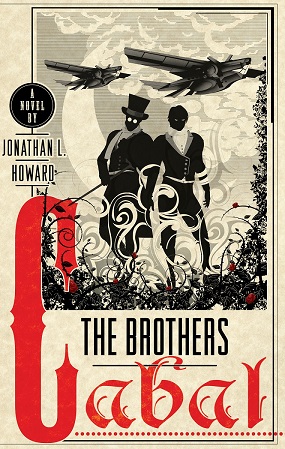

Read an excerpt below from The Brothers Cabal, the fourth installment in Jonathan L. Howard’s Johannes Cabal series—available September 30th from Thomas Dunne Books!

Chapter 1

In which the dead are raised,

blood is drunk,

and eaves are dropped.

The party travelled through the flatlands, guided by an unhelpful map. They were a sombre and sober group, ten men and three women, who wore hiking clothes and impressively stacked backpacks. An astute observer would have noted that their clothes and gear were all new, and that several showed signs of blisters due to their boots not being properly worn in, and that none looked happy in a woollen hat. There were no observers, however, for the flatlands are unutterably tedious and usually lacking in things worth the observing.

Their leader paused and consulted the map again. This took the form of a large square of predominantly blank paper upon which the legend and gridlines had consumed far more ink in the printing than any physical features. There were a few paths—even to call them ‘lanes’ would be an aggrandisement—a few ditches with pretensions towards being streams, and one long earthwork that travelled into the centre of the map and then petered out, as so many things in the flatlands tended to. Drystone walls, interest, lives… all fading away.

At least the earthwork had the decency to stick up: a long railway bed for a spur line to nowhere, abandoned decades before. They could see it was heavily overgrown on the steep sides of the artificial ridge, but there were also signs that, relatively recently, much of the heavier undergrowth had been cut back or felled. They clambered up onto its top, past the unhealthy bushes and saplings that grew there, and found themselves on the rail bed itself, still bearing—slightly surprisingly—sleepers and tracks. Even more surprisingly, there was a train there, hidden behind the trees and shrubs.

This discovery certainly surprised the hiking party, and even overawed them. The locomotive, although matte with rust the shade of dried blood, still exuded an air of exultant mechanical malevolence, as if somebody had crammed a black dragon into a giant jelly mould in the form of a steam locomotive and, with the wave of a wand, transformed the creature into the machine. But no; a wand would be insufficient. A magic staff perhaps. Or an enchanted caber. In any event, the iron dragon now slumbered in the sleep of years. Behind it was a train of assorted carriages, flatbeds, and freight cars, all once painted in black with red detailing, the exquisite work now peeling and forlorn. Just readable on the side of one of the cars was the legend The World Renowned Cabal Bros. Carnival.

The leader of the group looked at the words for a long moment, and then smirked a very superior smirk of the type that starts at the corner of the mouth and finishes with trouble.

‘This is the place,’ he said. ‘Start the search.’

The search went uncommented upon by passersby because there were no passersby. The flatlands went nowhere in either geographical or metaphorical terms, and no one went into them without the explicit intent to come out again, quickly. It was, in theory, an ideal place for footpads to operate, but the lack of potential victims had always kept its criminal population low, dwindling to none in relatively recent times. So there was nobody to see as twelve hikers, chivvied on by the thirteenth, dutifully dumped their packs, split the area into a search grid, produced strangely wrought weights on lengths of cord from identical pouches each had in their duffel coat pockets, and proceeded to methodically dowse the squares of the grid one by one. As an activity, it combined the mundane with the strange with the clandestine, and thereby rendered itself sinister. This was fair, for their intentions were sinister.

Nor was their apparent efficiency a chimera. Within ten minutes one of the hikers was excitingly calling to their leader. He came over, as did the others, to see the hiker’s plumb weight swinging in a manner harsh and angular, showing a brutalist disregard for physics that would have made Galileo enter the priesthood. They watched it twitch in silence, watched it marking out a pentacle in the air.

‘Here?’ whispered the hiker, aquiver with excitement.

‘Here,’ said their leader with magisterial certainty.

Again, their activities were efficient yet strange. Quickly they doffed duffel coats and woolly hats and map cases. Quickly they donned robes and then struggled to strip naked beneath them like a charabanc party changing at the beach of a Whitsun weekend. When the undignified hopping and kicking off of trousers was complete, they hastened to create a circle of blue powder about the spot they had detected, and then they gathered around it as the dying sun sank beneath the horizon. It wasn’t a happy circle—they were now all barefooted and the area was scattered with chippings from the rail bed—but it was a disciplined one, and they awaited the words of their leader.

When they came, they were incomprehensible.

‘Vateth He’em!’ he cried, excellent projection betraying a thwarted career in the theatre. ‘Oomaloth T’y’araskile!’ And so he continued, booming forth an apparently endless litany of dreadful names and imprecations from memory, all bedewed with apostrophes. The hikers-turned-cultists chanted the occasional response, a ‘Gilg’ya!’ here and a ‘Ukriles!’ there, and kept their eyes turned to the ground, for the grey skies were darkening and a wind was rising. Something was coming, and none dared to see its arrival.

Around them, the air swirled, centring upon the blue circle. The powder was blown, yet remained in the place, stray motes caught and carried back into it. The breeze was not dispersing the circle; it was concentrating it.

The landscape flickered under silent lightning, and those present scented a change in the air, a mixture of rage and blood that dizzied the mind and turned the stomach. Something wrathful was coming, a creature of death, and their fear was mixed with triumph, for all this was planned. The wind turned and dust was drawn in from their surroundings, drawn in from across the circle to grow in the middle, skittering particles the colour of bone, dancing from their hiding places between stones and from the soil itself. Nearby, a tattered and faded jacket fluttered where it lay at the base of the earthwork.

Then, with a roar that they felt rather than heard, the circle was filled, and they all fell silent in the awful presence, an aching tintinnabulation of the soul sounding a single peal within their hearts that turned their knees weak with dread as it faded.

‘Master,’ said the leader of the cultists. It came out weakly, his mouth and throat dry. He swallowed and tried again, stumbling over his carefully prepared words. ‘Master, you bless us with your baleful… personage. We fall in obeisance before you.’

It took a moment before they collectively realised that they’d forgotten to fall, and there were a few seconds of hasty kneeling and sharp intakes of breath as bare knees found jagged gravel.

The leader was belatedly realising that he could have organised the circle a little better before now and he was reduced to hissing urgently, ‘The sacrifices! The sacrifices!’ until the three women in the group were gathered before the monster in the circle.

‘Master,’ said the leader, eager to recover face, ‘Lord of the Dead. Please accept these sacrifices we humbly offer you, that you may feed and gain strength after your long and dreamless sleep.’ He lowered his head and hoped that three would be enough. Even among their fanatical ranks, it had proved difficult to find three who would willingly sacrifice themselves for the greater good.

Then the Lord of the Dead spoke.

And he said, ‘I won’t say I’m not a bit peckish. Famished, in fact. But not nearly as much as I’m surprised. And naked. I don’t suppose anyone thought to bring along a spare pair of trousers, did they? There are ladies present, and I was raised to believe that being naked in front of strange ladies is something reserved for special occasions.’

They had not, in fact, remembered to bring along any clothes for the Lord of the Dead, indicating another failure in planning that would later result in some sharply worded memos. One of the cultists was, however, about the same size as the Lord of the Dead, and was pleased to give him a change of clothes from his pack. The Lord of the Dead thanked him and promised that he would give them back, freshly laundered, as soon as he was able. The cultist said it was fine, really. The Lord of the Dead insisted, and also said that everybody should stop calling him ‘Master’ and the ‘Lord of the Dead’, and just call him ‘Horst’ instead, because that was his name.

‘My Lord Horst,’ said the leader, who was slightly scandalised that any puissant supernatural force of darkness and destruction should want to be on first-name terms so early in their acquaintance, ‘you must feed.’

It was true; Horst did not look well after his period as dust. His eyes were sunken deep within their sockets and bone showed beneath the parchment of his skin. He looked like a corpse in the mid-stages of mummification, and his borrowed trousers would not stay up without assistance.

The three women who knelt at his bony feet were quickly running through personal variants of ‘It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done’, and drew back their cowls and exposed their jugulars to him.

‘No,’ said Horst, shaking his head slowly, the best speed his desiccated neck could manage. ‘No, no, no. That’s not enough.’

‘Not… enough?’ The leader looked around the circle of his acolytes and saw faces as worried as his own. ‘How many will you require?’

‘Well, if I just feed from these three… Hello, ladies… I’ll kill them, and that’s not very polite. If I take a little from all of you, nobody has to die. I’m sure everybody would be happier with that, don’t you think?’

The leader was slightly baffled. ‘But, master…’

‘Horst.’

‘My Lord Horst, you are the embodiment of Death. You live without breath or vital spark in the umbral shadows, you are the wolf that preys upon we mortal cattle, you are…’ The leader’s voice was no longer very magisterial, just petty and wheedling. ‘Well, you’re a vampire, damn it. We brought these three here specially.’

‘I’m sure their mothers… Hello, ladies… didn’t raise them to be all-you-can-eat buffets. As for me, I’ve beaten up a few people in my time, but I’ve never killed anyone. Never felt the need to. I’m not saying I’m incapable of it, but it’s not something I’ve ever really aspired to, yes?’

‘But you’re the Lord of the Dead!’

‘No,’ said the monster in the loose clothes. ‘I’m Horst Cabal, and I don’t murder for the sake of a snack. Now, as you pointed out, I need to feed. I shall only take what each of you can spare.’

The leader was feeling peevish that the sacrifice that he had so selflessly ordered others to make was being snubbed. ‘We dragged those three all the way out here for nothing,’ he muttered furiously under his breath. Unhappily for him, inhumanly sharp senses are common amongst vampiric folk.

‘I think,’ said Horst, regarding the leader with a wolfish expression, ‘we’ll start with you, shall we? Leading from the front, and all that.’

‘Me?’ The leader was certainly intending to protest in the strongest terms, but then he made the mistake of looking at Horst’s eyes and whatever he had been intending was lost in a sudden simplification of his mind’s working.

Horst flicked back the leader’s cowl with an offhand gesture, took hold of his hair, and pulled his head back to expose his throat. ‘Yes. You.’ Horst’s lips parted and unusually long canine teeth showed as he leaned in. He paused and said to the silent onlookers, ‘The rest of you, form an orderly queue.’

About halfway through the ad hoc transfusion session, Horst noticed that those that had already donated were clearly envied by those that hadn’t, and those that hadn’t were being patronised by those that had. He wondered vaguely if, in the time he had been away, vampirism had become fashionable. How long had he been away, exactly?

He was feeling sated before he had finished with the ninth. Not completely revivified, he knew, but he was conscious of taking too much too quickly. He had been careful the first time he had drunk blood, and that had proved wise. It would prove equally wise to stop now, but then he looked at the faces of Victims 10–13 and felt he couldn’t let them down. Sighing inwardly, he finished with 9 and wearily gestured over 10. It would just be a nip, but at least duty would be honoured. His situation was not improved by 13, the third of the women, who insisted on making orgasmic noises at the first graze of his fangs. Under the circumstances, it seemed ungentlemanly to be perfunctory, and so he soldiered on until she’d run out of expressions of passion. He straightened up, feeling replete, reborn, and generally resanguinated, but also irked that performance anxiety should pursue a fellow beyond the grave.

‘So,’ he said as the cultists—practically, if unromantically— passed around a box of sticking plasters, ‘now what?’

‘We must take you to the castle with all dispatch, my lord,’ said the leader, who it transpired was called Encausse.

‘The castle. Of course. Should have known there would be a castle involved. Which particular castle would that be?’

Encausse looked uncomfortable, and Horst guessed he was wrestling between a conspirator’s natural desire for secrecy and a conspirator’s equally natural desire to tell everyone how brilliant the conspiracy is. ‘I am not permitted to say, my lord.’

Horst considered softening his mind a little until the concept of ‘permission’ became more malleable, but reined in the impulse. After all, that was the sort of thing real monsters did, and Horst didn’t care for it.

‘Well, is it far?’

‘Yes, my lord. It will take several days to transport you there. I am sorry.’

‘For what?’

‘The inconvenience.’

Horst looked down at his newly reconstituted hands, and rubbed them in the manner of one getting down to brass tacks. ‘The inconvenience… Well, don’t be too hard on yourself. You’ve resurrected me, which was decent of you. We’ll just consider ourselves even between that and the inconvenience.’

Horst was finding all manner of things not to like about the situation, and nestling high upon the parapets of his misgivings was why such a band of well-equipped and well-informed eccentrics had gone to all this trouble in the first place. For the first time he felt a small pang in his slowly beating heart. He hoped Johannes was still alive somewhere and he wished he could be here. All this occult malarkey was much more his brother’s meat and drink. Johannes would have identified the group concerned, insulted everyone, and probably settled into a spirited gunfight by this juncture. The pang troubled Horst again; to his profound surprise, he was missing his brother.

He looked at Encausse and saw the man was nervous. Horst guessed he’d got it into his head that vampires kill people willynilly for every little disappointment. Perhaps they usually did. How would he know? Nobody had ever given him an induction lecture or even a pamphlet on the subject. He spoke to defuse the tension as much as anything. ‘And how do you intend to get me to this castle? I think my passport has probably run out by now and, anyway, wouldn’t being dead invalidate it?’

Encausse waved away the point, his relief at not being summarily murdered clear. ‘All is in preparation, my lord. The means to transport you are at hand.’

Horst looked around. They didn’t seem to be that at hand. He looked quizzically back at Encausse, who smiled awkwardly. ‘Not exactly here, that is. But there is a small port a mile or two away to the west. There, the means to transport you are at hand.’

At least, thought Horst, the man hadn’t added ‘…honest’ at the end of the sentence, and thereby undermined all credibility.

As it turned out, however, planning was clearly a strong suit with whatever organisation had decided to, for reasons that currently remained obscure, locate the place of Horst’s second death by means that remained obscure, resurrect him by means that also remained obscure, and then blithely offer him three lives. Three volunteered lives at that. As the lid of his beautifully appointed coffin closed upon him, Horst wondered if he was doing the right thing going along with them. Escaping his honour guard would have been simple, yet it would have left him with no answers, and he had a feeling that answers might be important, and not only to him.

They had a castle, for heaven’s sake. A castle. From his conversations with Johannes, Horst had received the impression that most occult groups might stretch to hiring the local Scouts’ hut monthly for their meetings under the pretence of being philatelists or something. A castle made things seem very well funded. Also, Encausse had dropped enough hints to confirm to Horst’s satisfaction that the thirteen cultists were by no means the entire strength of this particular organisation. Between all this and their singleminded desire to avail themselves of a ‘Lord of the Dead’, he was sure their aims were not at all philanthropic and that they deserved whatever scrutiny he might bring to bear upon them. Being a vampire didn’t mean he couldn’t be socially responsible. If things turned unfriendly, he was confident he could light out of the proceedings before the unfriendliness manifested in the form of a stake through the heart, he would find some way to report the affair to the forces of law and order, and his curiosity and conscience would be assuaged.

This was his plan, simple to the point of barely being a plan at all. Still, as he reassured himself, it wasn’t as if he was busy doing something else.

His coffin was loaded aboard a train at the head of the flatland’s spur line; the track there not having been certified as safe for some time, the points at the junction were locked against it. They travelled through the night in a secure baggage van, and Horst was able to stretch his legs in the company of Encausse and some of his entourage. The thirteenth donor sat on some mail bags and regarded Horst silently the whole night, biting her lip now and then. Horst returned wan smiles and felt more awkward about the situation than a Lord of the Dead probably ought. He was relieved when dawn approached and he was able to return politely to his coffin with expressions of regret that he in no way felt.

Encausse had told him that they were heading to the port before embarkation for the rest of the trip. Horst had naturally assumed he would awaken at the next dusk aboard a ship. Ideally not one called the Demeter; it never pays to tempt fate. He was therefore, astonished, delighted, and yet slightly disturbed to find himself aboard an aeroship, the Catullus, a relatively small but well-appointed pleasure yacht apparently donated or lent to the cult by one of its supporters. Horst was astonished because he had naturally understood the port they were making for to be a coastal one, not an aeroport, delighted because he had never been aboard such a vessel despite years of yearning, and disturbed because, once again, his benefactors seemed to have very deep pockets indeed.

Benefactors. No, that was looking very unlikely in itself. Presumably the bill for all this largesse would be presented on arrival at the castle.

The journey was eastwards; that much at least was apparent, and they had crossed the Channel onto the Continent as he slept the first day. Encausse was still evasive about details, and—for the moment at least—Horst was still reluctant to use methods of persuasion more supernatural than gentle nagging. For the moment at least.

Only Encausse’s two lieutenants had joined them aboard, leaving Horst’s admirer behind. This relieved him greatly. It would only have been a matter of time before he would have awoken one evening to find her fluttering around his stateroom in a peignoir, draping herself over the furniture here and there like a particularly available moth, and his life was complicated enough as it was.

The crew was small, and taciturn to a man. They wore black uniforms without any insignia at all, only the design of the clothes serving to designate rank and role. Horst, who had an eye for such things, noted the paramilitary styling of the uniforms and the distinctly Teutonic aesthetic informing them, and wondered if he was bound for the Germanys. He imagined the coincidence if they were to set down in Hesse, his homeland. He could drop in on his mother. And probably put her in her grave with shock. No, perhaps that wasn’t the best idea. His former life was gone, twice over. That Horst Cabal only lived on in memoriam and legal declarations of death in absence of a body.

So he sat silently in the yacht’s small but extravagantly appointed salon, watched the clouds go by, and accepted that he wasn’t really Horst Cabal at all, but just an echo of a slamming crypt door. He was aware of being observed at such times by Encausse and his people, and observed approvingly. The more laconic he became, it seemed, the more seriously he was taken. Certainly his brown studies were far more in keeping with the image of a saturnine Lord of the Dead, so he maintained them even when his spirits rose.

Instead of engaging his keepers in conversation, he amused himself by practising the abilities that had replaced such trivial things as being able to walk in direct sunlight without messily combusting. He did not care to practice the placing of the human will into neutral—it was too addictive a sensation—but he had always taken some pleasure in the remarkable bouts of speed of which he was now capable. They were short, a matter of seconds, but for those few seconds he could travel with such speed as to become momentarily invisible. This he tried and was pleased to discover he still did easily. Indeed, there was a distinct impression of improvement, which perplexed him. Where before he had found it necessary to apply himself carefully to navigating around obstacles, now it seemed so instinctive as to be reflexive. He hypothesised two possible reasons. Firstly, in his first bout of being vampirically inclined, he had been nervous about taking too much from any single donor in case he seriously weakened or, heavens forfend, killed them. His current experience, he realised, was the first time he had ever been truly replete. It made him feel powerful. It made him feel very good indeed.

The other theory was that, in conversation with his brother, Johannes had made reference to a steady increase of puissance throughout a vampire’s existence. Did that existence include periods as dust? Perhaps so. In any event, he found it child’s play to be out of his chair and into the corridor behind the sidekick of Encausse who had been surreptitiously watching him.

Horst saw the man start, heard him gasp, and smelled the adrenaline suddenly flush his system. The man reflexively turned to scan the corridor behind him and looked straight at Horst. Another little gift of the vampiric unlife was that of psychic invisibility. Horst pushed himself out of the man’s perception and the man accepted him as something of no interest. Indeed, with an irritated grunt, the man leaned to one side, looking past Horst as he looked for Horst. ‘Where the hell has that bastard leech gone?’ he muttered, proving that eavesdroppers seldom hear well of themselves.

As the man scurried into the salon to search behind the bar, under chairs, and beneath the cushions, Horst strolled forward at a more human speed, but still repressing his presence.

He heard voices and found them coming from the ventral observation room, a small chamber protruding slightly from the yacht’s belly, glass walled and floored but for a solid section on which were arranged a cluster of armchairs. The intention presumably was for the owner and his or her guests to gather here to look down on the world below, literally and figuratively. At night, however, the view was unengaging even to Horst’s sharp eyes. Occasionally the lights of a town might go by below, but otherwise the nocturnal landscape was disappointing.

Encausse and his other lieutenant were sitting there and watching the darkness, a half-empty bottle and a pair of wine glasses sitting on the table between them. ‘… set up for a fall,’ Encausse was saying. ‘I’ve got a couple of people who’d love to see me look a fool.’

‘Von Ziegler,’ offered the lieutenant, a surly man called Donner.

‘Von Ziegler for one, arse licker that he is. I can’t see how they can blame me, though. The mission’s a success. We have the vampire, alive and… Well, you know what I mean. Up and around. Not what I was expecting, though.’

‘Not what any of us were expecting.’

‘Did you hear what he said? He’s never killed anyone. What kind of vampire’s never killed anyone? I don’t understand why he was chosen. There must be others, mustn’t there? Even if they’re dust, we can still raise them. Vlad Țepeș. Lord Varney. And we end up getting Count Form-an-Orderly-Queue.’

He touched the side of his neck and winced at the memory. ‘Ours may not be to reason why, but I cannot help but wonder if the Ministerium hasn’t made a mistake.’

Horst raised an eyebrow. The Ministerium? Interesting. Very interesting. He had no idea what it meant, but that didn’t stop it being interesting.

‘I thought the order didn’t come from them?’ said Donner.

‘What?’ Encausse was taken aback. ‘Of course the order came from them.’

‘Well, maybe via them,’ conceded Donner. ‘I thought Her Majesty insisted.’

There was a definite sneer in Donner’s voice, and Horst wasn’t sure if the honorific was meant sarcastically or not. But then Encausse replied, ‘The queen wanted him?’ He sank back in his chair and took a draft of wine that was an indecent use of a good vintage. ‘I didn’t know. I didn’t know. I just thought… We fulfilled our orders to the letter. It’s not our fault the “Lord of the Dead” is a namby-pamby, is it?’

Donner shook his head. ‘We did as we were told. She was the one who did the choosing. She picked him, he’s her problem.’

Encausse seemed reassured by this line of reasoning. ‘Yes, true enough. We didn’t choose him. I’d have gone for a proper nosferatu if it had been left to me, not that bloody fop.’ Horst raised both eyebrows; spying was turning out to be quite hurtful to one’s feelings. ‘But what the queen wants, she gets, and she can’t blame anyone else if that’s a bad choice.’ A pause, and he added a little shakily, ‘Can she?’ He took another gulp of wine.

‘Wouldn’t worry about it. She’s hardly there most of the time. By the time she turns up again, his nibs will be the Ministerium’s problem. How he got from where he was to where he is won’t matter anymore.’

Further reassuring noises from Donner were interrupted by the arrival of the other lieutenant, Bolam. ‘He’s gone! He was in the salon and he just vanished! Poof! I was looking right at him! I can’t find him anywhere!’

The ensuing search was short and confusing for Bolam, as the missing Horst was found to be exactly where he was supposed to be, in the salon, watching the darkness through the aft windows.

‘Is there a problem, gentlemen?’ he asked as the three men burst through the door.

As dawn approached, he was escorted to his coffin perhaps more assiduously and with far more narrow-eyed suspicion than previously. To these unfriendly airs he seemed blithe and friendly, but he was markedly aware of them all the same and wondered how the night’s events might have altered their perception of him. Momentarily, he remembered standing behind the astonished Bolam, and the thought of how easily he might have reached out and snapped the man’s neck flittered across his mind. Before he could quell it, there was the flickering beginning of the next idea to follow on, a spectral carriage in a ghost train of thought. He saw Bolam’s exposed neck, saw the blood in him. How easy to drain, kill, and fling the corpse from the aeroship.

Horst paused by the coffin in the small, windowless freight hold as Bolam and Donner lifted the lid off. Encausse saw his face tighten and watched with concern as Horst swayed a little.

‘My lord? Did we leave it too close to daylight? Are you well?’

Horst swung his head sideways to look at Encausse. There was something dreadful burning in Horst’s eyes that made Encausse take a sudden breath in surprise and even fear, a sullen, dark fire that had no place in the face of anything human.

‘When we arrive,’ said Horst, and his voice was grating and unfamiliar even to him, ‘I will require blood.’

‘Yes.’ Encausse blinked quickly. He had a growing sense of danger of a sort that was alien and terrible to him. ‘Yes, my lord. It will be arranged.’

Horst shifted his gaze forward, and Encausse felt he could breathe more easily again. Horst stepped quickly into the coffin on its low bier, settled onto his back, and, for the first time Encausse had seen in their short acquaintance, crossed his arms across his heart. Scowling, Horst closed his eyes very positively, dismissing them with contempt by the action. Bolam and Donner were very happy to replace the coffin’s lid, and the three of them left the hold with haste.

They closed the hatch behind them and, without thinking, Encausse locked it—another first. He looked at his lieutenants in silence for a moment and saw that they were as pale as he felt.

‘Well,’ he said at last, unsurprised and unashamed by the waver in his voice. ‘Perhaps the Red Queen knows her business after all.’

The Brothers Cabal © Jonathan L. Howard, 2014